I don’t consider myself old, just temporarily sidetracked. While I’m aware the only time I’ll lace a double down the right field line again is in my memory, I still held out hope, until recently, of cranking a 250-yard drive down the center of the fairway. But at what point do we eventually acknowledge our youth exists only in the rear-view mirror? I have a couple theories on aging especially for guys who know they’ll never get old. In other words, all of us.

I remember a glorious late spring afternoon some 15 years ago, sitting out on the patio of a downtown Armory Square pub in Syracuse, New York, enjoying a cold one with my dear friend Mike and some of his fellow middle school teachers. A few of them were teasing one young teacher in her mid-20s about her social life. After a few humorous barbs, she shared one particular frustration.

“I don’t get how these 50-year-old guys think they have a shot with me,” she exclaimed.

Since she didn’t know me from Adam, I bit my tongue. But as a then-50-year-old guy, I actually did have was a couple of answers. One of them was a dive into the male psyche.

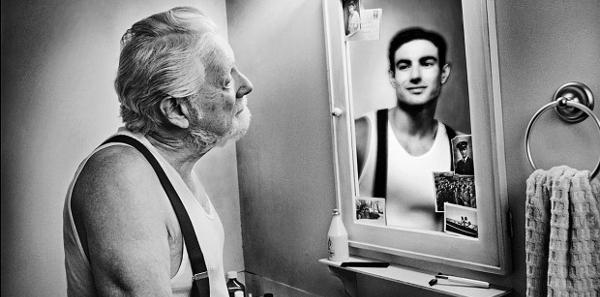

“Old guys” who chase pretty, young women do so because that’s who they chased when they were young. Since we all actually think we are still young, why not? Looking in the mirror each morning, that hint of gray at the temples is an anomaly. The crow’s feet around the eyes are from too much sun last week. And the hairline isn’t any farther north at all. Since we haven’t gotten any older, why not chase women who are young, too?

Denial in excelsis.

I believe that type of denial, though, has a basis in reality. Deep in our innermost being, we believe all of our aches and pains, all of our maladies and diseases, are just temporary. That’s because innately know our bodies are just earthly holders for the spirit-beings we really are. Since we’re made in God’s image, our new spirit-bodies will be transformed. Perfect. Beautiful.

Until then, we’re stuck with the bodies we have. We can watch ballgames on TV and delude ourselves into remembering when we made plays “like the pros.” We can live vicariously through the exploits of our kids and grandkids. We can call on all the sweet (um, enhanced) memories of our youth.

But through that denial, here’s a bit of reality. To get that heavenly body, we need to actually make it to heaven. While I have no plans to trade in these used bones any time soon, my neurosurgeon has waved an obligatory red flag. After 40+ years of trouble, I’m finally getting my back fixed. Surgery tomorrow morning. I’m crossing my fingers I’ll end up 6-7 inches taller! Oops – there’s that denial again. Okay, maybe just 2-3 inches taller.

Prayers are welcome, of course, but here’s something even better. Set your own sights on heaven so someday, many years from now, we’ll be able to marvel at each other’s perfection. And maybe even play a heavenly round of golf!